You Can't Spec Your Way Out of Uncertainty (And What to Do Instead)

"Hey everyone, we're all here today, reunited to define (I mean, refine) together what's gonna go on the roadmap for the next quarter. If you please, I'd like each one of you to provide an estimate for all tasks in the backlog that I have prioritized after my thorough analysis that I've done in the last 2 months."

This is what I had to deal with at every single company I joined. The very same companies that defined themselves as "agile." The ones that believe in "ownership" and "autonomy." And yet here's the PM, messenger of the word of stakeholders and customers, asking us developers how much effort something is going to take for the next 4 months.

Let's talk about how agile failed to keep its promises, and confront that ugly concept called "uncertainty."

Agile was born to challenge the structured, bureaucratic processes that permeated software engineering up to the 90s (and still do at some companies today). It was the tool that should have helped manage uncertainty in an increasingly complex (if not chaotic) world that was still figuring out the World Wide Web.

The problem is, biz people never liked uncertainty so much (you know, investors, big egos), so agile had to squeeze itself into the cracks between sprints.

Unfortunately for the uncertainty-allergic people, the whole history of product development has been one of increasing uncertainty, and the present isn't looking any safer.

Why Handoff-Based Teams Fail at Uncertainty

So how did we respond? By splitting the work across specialists. PM handles the "what," designer handles the "how it looks," engineer handles the "how it works." Handoffs at every stage. In theory, each domain gets the attention it deserves. In practice, the handoffs create more problems than they solve.

PMs are the bottleneck. In most companies, PMs juggle multiple initiatives, multiple stakeholders. They become the central node everyone depends on for decisions, context, and prioritization. When one person is spread across five initiatives, four of them are always waiting. This creates a single point of failure disguised as collaboration.

The overhead is real. Three specialised roles means coordination cost. Meetings multiply. Calendars fill with syncs, stand-ups, and alignment sessions. Every decision requires getting three (usually more) people in the same room, or worse, the same Slack thread. The bigger the organization, the worse this gets.

Information dies in transit. Watch what happens when a designer explains a user flow to a developer. Something gets lost. Watch the developer explain technical constraints back to the PM, and more disappears. By the time decisions filter through the telephone game, the original context has been diluted, misunderstood, or forgotten entirely. Handoffs aren't just slow, they're lossy.

As PostHog's James Hawkins puts it, engineers end up with "a sanitized version of the truth" and don't have the right information to make the best decisions.

Chemistry makes or breaks everything. Handoff-based teams only work when people genuinely get along, when they're open, respectful, and willing to challenge each other without ego getting in the way. When that chemistry doesn't exist, I've seen talented individuals produce mediocre work together because the interpersonal dynamics were off.

Maybe that’s why at times, collaboration sucks (hard)

Local optimization creeps in. Each specialist naturally wants to perfect their domain. The designer obsesses over pixel-perfect interfaces. The developer optimizes for clean code and architecture. The PM builds elaborate roadmaps. Each piece might be excellent in isolation. But product coherence suffers when everyone's looking at their own slice instead of the whole.

These structures were designed to reduce uncertainty through specialization. Instead, they just spread it across more people.

The Shift: From Avoiding to Mastering

Traditional teams treat uncertainty as the enemy. They try to eliminate it through planning, documentation, and handoffs: detailed specs, elaborate roadmaps, sign-offs at every stage. The logic seems sound: if we define everything upfront, nothing can go wrong.

But uncertainty doesn't disappear when you document it. It just hides until implementation, when it's expensive to address.

Here's the alternative: one person who owns the full loop, from problem discovery to shipped solution, can move through uncertainty faster than any handoff-based team. No information loss. No waiting for the next sync. No translation errors between disciplines.

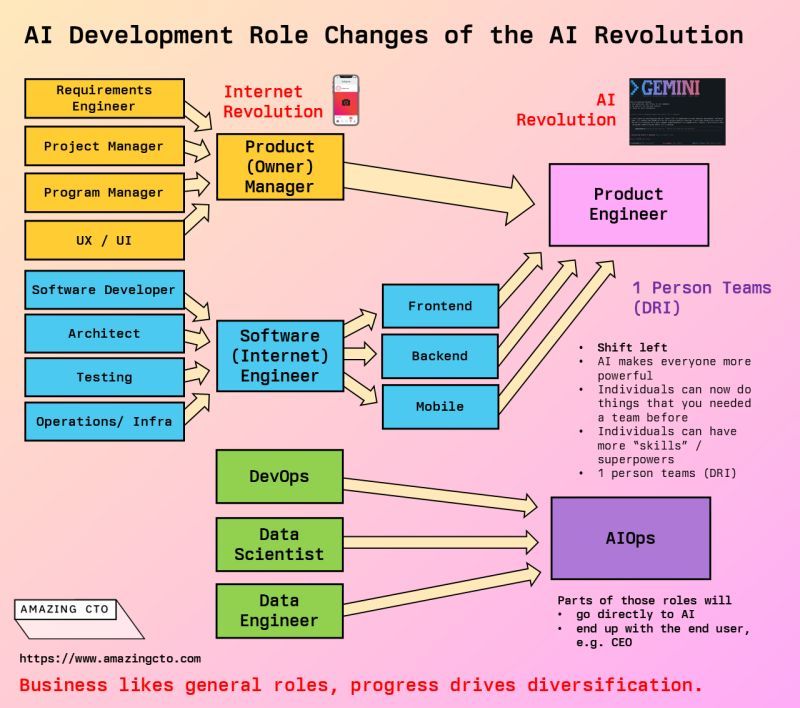

A great infographic from Stephan Schmidt, https://www.amazingcto.com

Picture uncertainty as fog over the path forward. One solution will emerge, but only through systematically clearing that fog. The question is: who's better equipped to clear it? Three specialists passing notes to each other, or one person who can see the whole landscape?

That's exactly why I started Product Engineers. Head over to http://productengineers.com for stories, opinions, and the occasional rant. Or subscribe if you want this stuff in your inbox.

Masters of Uncertainty

The job of a Product Engineer is to reduce the chance of building something that doesn't solve the right problem in the right way, while navigating the uncharted space where the map hasn't been drawn.

They aren't handed "build SSO," they're handed "enterprise is churning," and they figure out why. Maybe it's SSO. Maybe it's onboarding. Maybe it's permissions. The PM brings the business problem, and the PE owns problem discovery within the product and solution design.

In practice, this means testing bets before going all-in:

- Assumption testing and experimentation

- MVPs, PoCs, prototypes

- Customer and user conversations

- Concierge tests, Wizard of Oz experiments, and the full Lean Startup toolkit

Anything that avoids wasting resources on things that might not work.

They own the user experience, from accessibility to interaction design, and they implement it themselves.

Wireframes and code are tools, not the definition of the role. A PE might code a solution from scratch, use a no-code platform, integrate an existing solution, or do whatever solves the problem most efficiently. The focus isn't "I do product plus design plus engineering" but "I solve product problems, using whatever tools make sense."

Flexibility, reducing uncertainty, solving the problem efficiently. That's the point.

Teams Built for Uncertainty

One person owning the full loop doesn't mean everyone works alone.

Working solo works for some problems, but isolation has costs. When everyone finds problems independently and solves them alone, the product starts diverging. Features feel disconnected, and the overall experience loses coherence.

The better model: small, dynamic teams that form around problems. Kevin Östlin, co-founder of Andsend, calls these "product groups." Two or three people who own a problem together, end-to-end. More about Kevin's story here.

Here's the key insight: this isn't pair programming, it's pair everything.

The same people research together, hypothesize together, design together, build together, and evaluate together. No handoffs within the team because there's nothing to hand off. Everyone has full context because everyone was there.

These teams form fluidly. Someone identifies a problem worth solving and shares it with the team. Others who find it interesting join. The group tackles it together, ships, measures, then reforms around the next problem.

This is fundamentally different from traditional team structures. In the old model, teams were permanent. You were assigned to "Team Payments" or "Team Onboarding" and stayed there until someone reorganized. The team's scope was predefined, the roadmap handed down.

In the new model, teams are temporary coalitions formed around problems. The problem defines the team, not the other way around. Once solved, people disperse and regroup. The org chart becomes fluid, almost irrelevant.

The daily standup becomes a mini planning session. What did you ship yesterday? What hypothesis are you testing today? Who wants to team up on this problem you found?

No more uncertainty avoidance.

No planning rituals, just alignment.

"But This Doesn't Scale"

I hear this objection constantly. Sounds great for a startup, but surely this falls apart when complexity grows?

What changes is scope, not philosophy.

At a startup, a PE might own the entire product. At a larger company, they own a specific domain or problem space. The scope shrinks, but the workflow stays the same. The core unit is the team, a few PEs working on a defined problem space. As the company grows, you add teams, not layers.

It's exactly like Product Managers. A PM at a startup owns everything. A PM at Google might own how well a button color performs. Same role, different scope.

The org structure has to evolve too, though. Same problem as Agile. Companies say they're "Agile" but only dev teams run sprints. Meanwhile, business still does long-term roadmaps with specific features to build. That's not Agile, it's theater. Same trap here. If you have Product Engineer teams but leadership still wants to hand down features to build, it won't work.

Honest caveat: this is mostly startup and scale-up territory for now. AI-native companies will grow and establish new ways of working. Established companies with decades of ingrained processes won't flip a switch overnight, but the pressure will build as smaller teams consistently outship them. The rest will follow or fall behind.

When one aspect of a product needs to be done really well, not just good enough, you bring in specialists. A cybersecurity product needs security experts. A fintech product needs people who understand compliance deeply. Specialists for deep expertise, PEs for the product work. They coordinate, not replace each other.

Domain experience matters too. A PE who's worked in banking before is more valuable to a bank than one who hasn't. Same as PMs: product managers who've worked in banking get hired by other banks. The generalist skillset of a PE combines with domain expertise to create real leverage.

Why This Is Happening Now

Product Engineers existed before AI. PostHog pioneered the model. Ghost, Ashby, others were doing it too. Companies proved this could work before ChatGPT existed. But before AI, things were slower, especially the discovery phase. Prototyping took longer. Writing code took longer. The idea was there, but the friction was high.

AI removed the excuse.

Post-ChatGPT, post-Copilot: engineers are expected to work across more languages, use more tools, take on broader responsibilities. The specialist whose entire job is writing CI scripts or tuning database queries is in a tough spot. Any competent engineer can now do that work with AI guidance.

For Product Engineers, AI makes navigating uncertainty cheaper. Less time on code mechanics means more bandwidth for the uncertainty work: discovery, hypothesis testing, rapid iteration. Prototype an idea in hours instead of days. Test an assumption before committing to it. AI acts as glue, holds context, and enables coherent decisions across the stack.

We're knowledge workers navigating uncertainty. LLMs shine at exactly that: holding context, surfacing patterns, helping you think through the fog. As long as you have strong foundational knowledge, AI becomes a sparring partner that helps you explore faster. Technology becomes a means to an end, not the end itself.

One person can now do what required three. Not because they're a unicorn, but because the tools caught up. The fog clears faster when you don't have to schedule a meeting to discuss what you found.

The Builder's Mindset

Product Engineers aren't a rejection of expertise. They're a rejection of fragmentation, and an embrace of the discomfort of not knowing.

The difference isn't skill breadth. Plenty of developers know some design, some product thinking. The difference is how they relate to uncertainty. A developer wants clear requirements before starting. A Product Engineer is comfortable in the fog because they know clarity comes through building, not before it. They feel ownership over outcomes, not just outputs.

There's a professional pride at stake. They want to put their name behind great products, not just ship code that someone else designed. When a feature fails, they don't blame the spec—they never expected certainty from a spec. They ask why they didn't catch the problem earlier.

The organizations that figure this out first will move faster. AI-native companies are already hiring this way: fewer people who can do more. The rest will catch up or wonder why their fully-staffed teams keep getting outshipped by three-person startups.

What This Changes

The meeting I described at the start, the PM asking for estimates while the roadmap was already decided, that whole "agile" theater? It's not going away because companies read a blog post. It's going away because the teams that reject it will outship the teams that don't.

The question isn't whether you have the skills. Plenty of developers already think about product. Plenty of PMs already get technical. The question is whether you're willing to own the uncertainty instead of hiding behind process.

Specs won't save you. Handoffs won't save you. The fog is the job, and the people who learn to navigate it will build the things that matter.